|

||||||||||

|

|

Our Economy: More InformationThe following information, references, and web links are provided so that you can learn more about the economic importance of clean boating. U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, and U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. 1996. 1996 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation. U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, DC. Our Family's Health and Safety: More InformationDisease-Causing MicroorganismsAmericans continue to face risks of illness from swimming and other recreational activities in coastal areas, lakes, and rivers that are contaminated with disease-causing microbes. While there is no true measure of all adverse effects, epidemiology studies in the U.S. and abroad have consistently found an association between gastrointestinal illness and exposure to contaminated recreational waters. Local monitoring and management programs for recreational waters vary widely, which results in different standards and levels of protection across the country. EPA is taking a role in assisting state, tribal, and local authorities to strengthen their programs to protect users of recreational waters, through its "Action Plan for Beaches and Recreational Waters" (the "Beach Action Plan"). High levels of pathogens in recreational waters can increase human exposure through ingestion, inhalation, and body contact, thus increasing the risk of illness. Surveys and ongoing scientific studies continue to document the presence of, or the potential for, disease-carrying bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens present in local beach water, primarily from sewage and storm water runoff. Fecal bacteria have been used as an indicator of the possible presence of pathogens in surface waters and the risk of disease, based on epidemiological evidence of gastrointestinal disorders from ingestion of contaminated surface water or raw shellfish. Contact with contaminated water can lead to ear or skin infections, and inhalation of contaminated water can cause respiratory diseases. The pathogens responsible for these diseases can be bacteria, viruses, protozoan, fungi, or parasites that live in the gastrointestinal tract and are shed in the feces of warm-blooded animals. Concentrations of fecal bacteria, including fecal coliforms, enterococci, and Escherichia coli (E.Coli), are used as the primary indicators of fecal contamination. The latter two indicators are considered to have a higher degree of association with outbreaks of certain diseases than fecal coliforms and were recommended as the basis for bacterial water quality standards in the 1986 Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Bacteria document (both for fresh waters, enterococci for marine waters). The standards are defined as a concentration of the indicator above which the health risk from waterborne disease is unacceptably high. Standards for swimming in fresh waters have been set at bacterial densities less than 26 colony forming units per 100 milliliters for E. Coli, and less than 33 colony-forming units per 100 milliliters for Enterococci. In marine waters bacterial densities less than 35 colony-forming units per 100 milliliters will exceed swimming standards. The Clean Water Act has had a major, positive impact on the release of disease-causing microorganisms by point sources such as municipal wastewater treatment plants. Storms, however, often cause problems. Urban wet weather discharges result from precipitation events, such as rainfall or snowmelt, and include municipal and industrial storm water runoff, combined sewer overflows (CSOs), and sanitary sewer overflows (SSOs). Urban storm water runoff, which is often collected by storm drains and transported to receiving waters, contains pollutants that are accumulated as rainwater or snowmelt flows across roads and the surface of the earth. Such pollutants include oil and grease, chemicals, nutrients, heavy metals, bacteria, viruses, and oxygen-demanding compounds. CSOs occur during wet weather events in approximately 900 cities that have combined both sanitary and storm sewers, and contain a mixture of raw sewage, industrial wastewater, and storm water. CSOs have caused beach closings; shellfish bed closures, and public health problems. SSOs are raw sewage overflows from separate sanitary sewer systems and occur when the volume of flows in a sewer system exceeds its capacity due to, among other things, unintentional inflow and infiltration of storm water. Such inflow and infiltration can occur because of inadequate preventative maintenance programs and insufficient sewer rehabilitation. SSOs can also occur during periods of dry weather. EPA's National Water Quality Inventory, 1996 Report to Congress, notes that "pollution from wet weather discharges is cited by states as a leading cause of water quality impairment." EPA believes that urban wet weather discharges should be addressed in a coordinated and comprehensive fashion in order to reduce the threat to water quality, reduce redundant pollution control costs, and provide state and local governments with greater flexibility to solve wet weather discharge problems. Storm water runoff can carry millions of disease-causing microorganisms. For example, Kennedy (1995) found that the number of fecal coliforms in highway runoff ranged from 100 to more than 3,000,000 colony-forming units per 100 milliliters and that these values were typical for urban runoff in Texas. Weiskel and others (1996) determined that animal waste carried by storm water was the main source of bacterial contamination to suburban Buttermilk Bay in Massachusetts, contributing more than about 12 trillion colony forming units to the bay each year. These problems are small in comparison to the potential effects from combined sewer overflows (CSOs) and sanitary sewer overflows (SSOs), which discharge human sewerage directly to our nation's recreational waters. Boaters can be a part of the problem by releasing disease-causing microbes when sanitary waste is discharged improperly. Commercial and recreational boating plays an important role in American society. Unfortunately, without proper management, these activities can contribute to water quality degradation. One type of degradation is the increased concentration of fecal coliform bacteria (found in the intestinal tracts of all warm-blooded animals). The discharge of untreated or partially treated human wastes from vessels can contribute to high bacteria counts and subsequent increased human health risks, and these problems can be particularly bad in lakes, slow-moving rivers, marinas and other bodies of water with low flushing rates. Section 312 of the Clean Water Act helps protect human health and the aquatic environment from disease-causing microorganisms and hazardous compounds, which may be present in discharges from vessels by regulating appropriate treatment levels for different watercraft. How do you find out where it is safe to get out of your boat and swim? Look at the following information: The EPA has established a "BEACH Watch" website to disseminate information about beach water quality, click here. To get contact information for regional EPA offices, click here. For more information about wet weather flows, click here. Food Poisoning From Fish and ShellfishThe U.S. Surgeon General, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registration, and the USEPA have issued joint letters to health care providers and health care professionals warning of the toxicological dangers of fish consumption especially for children and women in their childbearing years. The EPA has also published National Listing of Fish and Wildlife Advisories and Should I Eat the Fish I Catch? (A guide to healthy eating of the fish you catch.) The following chemical-specific fact sheets are summaries of the most current information on sources, fate and transport, occurrence in human tissues, range of concentrations in fish tissue, fish advisories, fish consumption limits, toxicity, and regulations. The fact sheets also illustrate how this information may be used to develop fish consumption advisories. Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-dioxins and Related Compounds Update: Impact on Fish Advisories (PDF, 88K) Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) Update: Impact on Fish Advisories (PDF, 110K) Toxaphene Update: Impact on Fish Advisories (PDF, 81K) For additional information about fish toxicology programs, please contact: EPA Office of Water, Fish Contamination Program (4305), ATSDR, Division of Toxicology, MS E-29, Aquatic Debris HazardsAquatic debris is one of the more widespread pollution problems threatening our coastal waters and other aquatic habitats. Marine debris is trash floating on the ocean or washed up on beaches. Debris comes from many sources including beachgoers, improper disposal of trash on land, storm water runoff and combined sewer overflows to rivers and streams, ships and other vessels, and offshore oil and gas platforms. Once litter gets into the marine environment (marine debris), it seriously impacts wildlife, the environment, humans, and our economy. Thousands of marine animals are caught in and strangled by debris each year while coastal communities lose considerable income when littered beaches must be closed or cleaned up. The fishing industry spends thousands of dollars annually for the repair of vessels that are damaged by debris. The increasing number of people living near our coasts, which increases the amount of trash produced and entering the marine environment, compounds these problems. Synthetic materials (such as plastics) added to the solid waste stream are of particular concern because they remain in the environment for years. Reference MaterialThe following information, references, and web links are provided so

that you can learn more about your family's health and safety: Heal the Bay. 2000. Swimming in the Bay: Health Risks. Posted at http://www.healthebay.org Heal the Bay, Los Angeles, CA. Accessed May 15, 2000. Kennedy, Keith, 1995, A statistical analysis of TxDOT highway stormwater runoff: comparisons with existing north central Texas municipal storm water database - in press: North Central Texas Council for Governments 18 p. USEPA, 1997 Should I Eat the Fish I Catch? (A guide to healthy eating of the fish

you catch.): Brochure EPA Action Plan for Beaches and Recreational Waters National Listing of Fish Advisories USEPA, 2000,

Liquid Assets

2000: America's Water Resources at a Turning Point. EPA-840-B-00-001 Weiskel, P.K., Howes, B.L., and Heufelder, G.R., 1996, Coliform contamination of a coastal embayent: sources and transport pathways: Environmental Science and Technology, v. 30, no. 6, p. 1872-1881. For further information about the USEPA Beach Programs, please telephone 202/564-6787 . Our Environment: More InformationAir PollutionOf non-road sources, EPA has determined that gasoline marine engines are one of the largest average contributors of HC emissions. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1996 "Environmental Fact Sheet: Emission Standards for New Gasoline Marine Engines." EPA420-F96-012 (html file) EPA420-F96-012 (PDF file) Code of Federal Regulations, 1999 "Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for New Spark-Ignition Marine Engines," Amendments 40 CFR Part 91 as published February 3, 1999 in Federal Register. Miller, G. Tyler, Jr. 1990, Living in the Environment: An Introduction to Environmental Science. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1991 Guides to Pollution Prevention: The Marine Maintenance and Repair Industry.

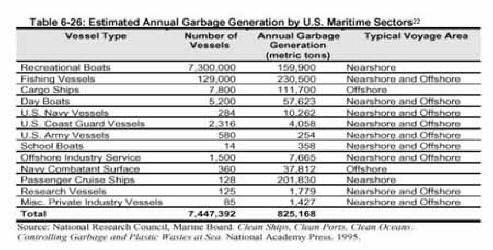

National Research Council, Marine Board . 1995, Clean Ships, Clean Ports, Clean Oceans: Controlling Garbage and Plastic Wastes at Sea. National Academy Press. Ingestion refers to instances in which animals swallow debris. The most publicized cases of ingestion involve sea turtles and cetaceans swallowing plastic waste. Ingestion of plastic and other debris can cause immediate death or result in a number of injuries or handicaps to wildlife. While very little data describes the extent of damage caused by ingestion, many anecdotal cases have been documented. It is estimated, however, that as many as 50,000 northern fur seals die annually from entanglement in plastic marine debris, primarily fishing nets and strapping bands. The amount of this debris attributable to vessels as opposed to land-based sources and other marine sources is unknown. Cases of entanglement have been recorded for 51 of the world's 312 seabird species and 10 of the world's 75 cetacean species. Ingestion of plastic debris has been recorded for at least 108 species of seabirds and 33 species of fish. Source: National Research Council, Marine Board. Clean Ships, Clean Ports, Clean Oceans: Controlling Garbage and Plastic Wastes at Sea. National Academy Press. 1995. Ghost fishing involves lost or discarded fishing gear that continues to catch finfish and shellfish. The extent of this problem is not well documented, but evidence suggests some lobster, crab, and other fisheries experience depletion due to ghost fishing. Lost or discarded trapping devices such as gill nets cause most of the problems from ghost fishing. SewageIn 1990, pollution from boating and marinas affected 25 percent of the harvest-limited shell fishing waters in half of the shellfish producing states (harvest-limited waters are those in which shellfish beds may be contaminated). Source: Council on Environmental Quality 1993, Environmental Quality Annual reports. In a survey of 3,561 miles ocean shoreline waters (in 11 states nationwide), marinas were reported to be a source of pollution on 116 miles, or 3 percent of surveyed miles. In total, 467 miles of ocean shoreline were reported as impaired. As a result, marinas were reported as a source of pollution on 25 percent of impaired river miles. This pollution could be from a variety of factors, including oil spills, sewage, and other waste. Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Appendixes from the National Water Quality Inventory: 1996 Report to Congress. Estimates of the total amount of sewage dumped by vessels in U.S. waters are not readily available. It is estimated that 90 to 95 percent of commercial U.S. vessels have marine sanitation devices on board. 75 to 80 percent of recreational vessels have marine sanitation devices on board. Source: U.S. Coast Guard. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1991, Guides to Pollution Prevention: The Marine Maintenance and Repair Industry. Clean Marinas: More InformationInternational Marina Institute, 1994. Marina Environmental Workbook. From a workshop sponsored by U.S. EPA, NOAA, and FWS. International Marina Institute. Marin County, 1994. The Marina & Boat Yard Waste Minimization Program, Final Report. Marin County Office of Waste Management, San Rafael, CA. Ohio EPA, 1995. Pollution Prevention for Marinas. Fact Sheet Number 30. Ohio EPA Office of Pollution Prevention. Ohio EPA, 1994. Pollution Prevention in Painting and Coating Operations. Fact Sheet Number 23. Ohio EPA Office of Pollution Prevention. Puget Sound Alliance, 1995. A Resource Manual for Pollution Prevention in Marinas. Puget Sound Alliance, Seattle, WA. U.S. EPA, 1991. Guides to Pollution Prevention - The Marine Maintenance and Repair Industry. EPA/625/7-91/015. U.S. EPA , Washington D.C. USEPA 1996, Clean Marinas Clear Value: Environmental and Business Success Stories US Environmental Protection Agency, EPA 841-R-96-003 For information on services available from marinas and boating trade associations: Lake Erie Marine Trades Association (216) 621-3618 Clean Boating: More InformationFOR MORE INFORMATION: Write to the U.S. Coast Guard (G-MOR-1), 2100 Second St., S.W., Washington, DC 20593, or e-mail lreid@comdt.uscg.mil and request "BOATERS PAMPHLETS". Water Watch: What Boaters Can Do To Be Environmentally Friendly, "National Marine Manufactures Association, call: 312-946-6200; single copies free; quantities at 25 cents each. Trash:Stow all loose items, plastic bags, drink cans, and other articles properly so they do not blow overboard. Never discard your garbage overboard. Whatever you take aboard, bring back. Under the Marine Plastic Pollution Research and Control Act, and the international agreement MARPOL Annex V, it is illegal to dispose of plastic, or garbage mixed with plastic, into any U.S. waters. The discharge of any garbage is prohibited in the Great Lakes and connecting tributary waters. Other Sources of Pollution: More InformationThe U.S. Environmental Agency has a great deal of relevant information that is free to the public. Much of this information is available from their Office of Water Internet Site . The United States Geological Survey also has a great deal of relevant information about water , maps and other topics . The U.S. EPA specifies management measures to protect coastal waters from sources of nonpoint pollution from recreational boating and marinas.

|

|

|||